Link to original article: GP stakes gain traction as fundraising slows

Private equity firms are taking stakes in their industry peers as a way to gain indirect exposure to their fund returns and balance sheets, and cash-strapped fund managers are happy to sell as they look for new ways to generate capital.

Through a GP stake, an investor takes partial ownership of a PE firm, granting access to the underlying business model and revenue from management fees. Meanwhile, a traditional PE investment—via a closed-end fund commitment—limits exposure to the returns that vehicle drives through its portfolio companies.

“There’s so much money moving from the public markets to the private markets,” said Christopher Zook, chief investment officer at CAZ Investments, a multifamily office based in Houston. “The way to benefit from that trend most directly is to own the firms that are getting funded.”

In recent years, investors have looked beyond PE as an asset class and considered it as a sector strategy for their portfolios. A GP stake gives the buyer access to the firm’s balance sheet—or the profits of the PE firm in its entirety—rather than limiting exposure to one fund. GP stakes also work as a strong diversification strategy for managers.

“When you buy a stake in a manager, you’re exposed economically to every single investment that manager has ever made that it still owns—and everything that it does off into the future,” said Sean Ward, senior managing director at Blue Owl, which recently closed its GP stakes fund Dyal Capital Partners V with $12.9 billion of committed capital.

Ward said he has seen a significant uptick in investor interest in the firm’s strategy over the past year as investors look to insulate themselves from a difficult economic environment.

At the same time, institutional investors are finding themselves overexposed to private market assets as a result of poor public equity performance, known as the denominator effect. As a result, the fundraising environment for PE firms becomes more challenging. From 2021 to 2022, total PE capital raised dropped almost $20 billion year-over-year, according to PitchBook’s 2022 Annual US PE Breakdown.

Depending on the degree to which fundraising slows in 2023, PE firms may look for alternative methods of raising capital—such as selling a GP stake—over the course of the next two years, said Lee Gardella, head of PE in North America at Schroders Capital.

“In the current environment, where institutional fundraising has slowed, GP stakes have always been a source of liquidity and capital for PE firms,” said Gardella. “It should help, to some degree, with fundraising.”

Specifically, the presence of an investor with a strong reputation and track record as a minority owner helps these firms generate investor interest and capital commitments in subsequent funds. The GP stakeholder can provide the firm with greater access to new distribution channels and capital sources, which is especially helpful to small and emerging managers that are already at a disadvantage in the current fundraising environment, according to MJ Hudson.

The largest PE players dominated fundraising in 2022. Mega-funds brought in 52% of total capital raised last year as LPs faced capital constraints and stuck to larger, more established managers, according to the US PE Breakdown.

This market split between mega-funds and smaller firms extends to GP stakes, Ward said. Blue Owl typically takes stakes in the larger firms: Fund V has made investments in 17 firms so far, including CVC Capital Partners ($148 billion AUM), PAI Partners ($28.5 billion), and H.I.G. Capital ($53 billion AUM).

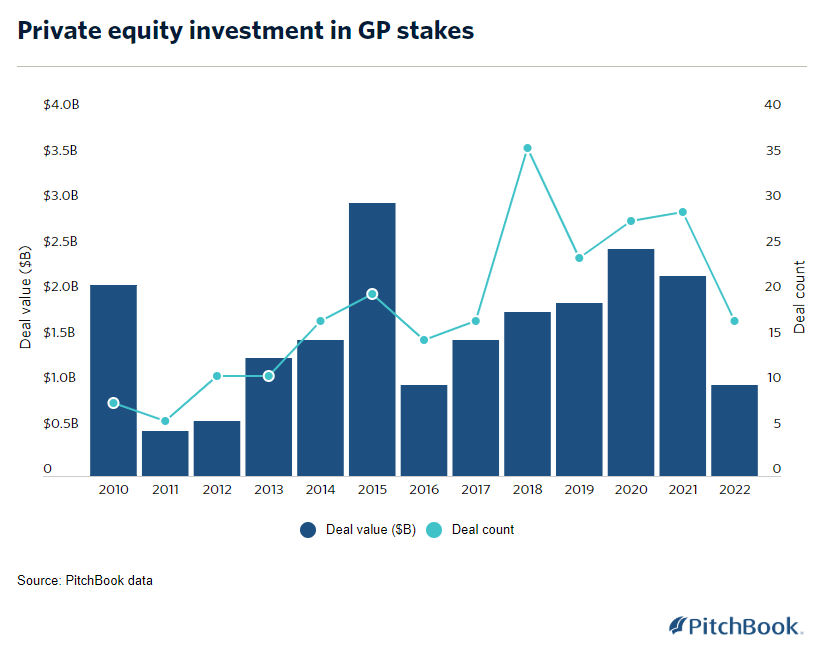

Still, deals involving GP stakes took a hit at the tail end of 2022 as the overall PE market suffered. From 2021 to 2022, total GP stake deal count dropped from 29 ($2.2 billion in total deal value) to 17 ($1 billion), according to PitchBook data.

According to Ward, large funds are generally able to raise capital even in difficult fundraising environments because mega-funds attract longer-term investors like public pension plans, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds, which are able to continue to to invest in private equity across an economic cycle. It’s also less risky to buy stakes in larger PE firms that have product diversification, a large client base and a proven track record, and are viewed as an important relationship by many of their investors.

“The investor mix is a bit more resilient for bigger firms, where we focus,” Ward said. “When you go down the size range to smaller mid-market firms and lower mid-market firms, or a startup, it’s much, much, much harder.”